2.6.3. Eventlog¶

Eventlog is a GHC runtime system feature that logs events at runtime of a compiled program. It provides runtime information on the heap, the garbage collector, the scheduler, and arbitrary events that a user inserts into their own code. Eventlog is a versatile profiling tool, and should be one of the first tools in the profiling toolbox you reach for. Use eventlog when you are just beginning to diagnose the problem and are gathering data. Specifically when you want to inspect the heap or some other subsystem, such as the garbage collector. This chapter walks through using eventlog to inspect a small program that suffers from Excessive Pointer Chasing. By the end of the chapter you should understand:

What information can you retrieve by using eventlog.

When to use eventlog.

How to build your program to use eventlog.

How to visualize eventlog information.

How to tune eventlog to inspect specific sub-system.

How to tune eventlog to inspect specific pieces of code.

2.6.3.1. Requirements¶

The program must be recompiled with the

-eventlogGHC flagA program to consume the

<program>.eventlogfile. We recommend eventlog2html; see also the relevant section in the GHC User’s Guide. You can also parse the<program>.eventlogfile using the ghc-events library.

2.6.3.2. Restrictions¶

Eventlog is portable, and should work anywhere GHC’s native runtime system will work.

2.6.3.3. What Information Do I Receive From Eventlog?¶

Eventlog logs events as a function of elapsed walltime. A full list of possible events is available in GHC User’s Guide. In general, the most common use case is to track heap events; which will be the focus of this chapter. However, a user may define and track their own events using the base functions traceEvent.

2.6.3.4. When should I use Eventlog¶

Eventlog is most useful when you need to characterize the problem. It yields

runtime information on the specific sub-system the program relies on. Thus, it

allows you to drill down into the behavior of the garbage collector, the

scheduler, the heap and so. For example, using the flag +RTS -lg you can

collect the CONC_MARK_BEGIN and CONC_MARK_END events which log the

beginning and end of the concurrent garbage collectors marking phase. Similarly,

you can collect MEM_RETURN which provides information about the current

allocation of megablocks, attempts to return them to the operating system, and

heap fragmentation.

2.6.3.5. The Running Example¶

We’ll use a toy program to demonstrate heap profiling with eventlog. Our toy program is an example of excessive pointer chasing and should be familiar to most Haskellers’ as a traditional example of a memory leak:

{-# LANGUAGE BangPatterns #-}

-- Need to disable optimizations because GHC will recognize and perform

-- let-floating for us!

{-# OPTIONS_GHC -O0 -ddump-simpl -ddump-to-file -ddump-stg-final #-}

module Main where

import Data.List (foldl')

import System.Random (mkStdGen)

import System.Random.Stateful (newIOGenM, uniformRM)

import Control.Concurrent (threadDelay)

import Control.Monad (replicateM)

lazy_mean :: [Double] -> Double

lazy_mean xs = s / fromIntegral ln

where (s, ln) = foldl step (0,0) xs

step (s, ln) a = (s + a, ln + 1)

stricter_mean :: [Double] -> Double

stricter_mean xs = s / fromIntegral ln

where (s, ln) = foldl' step (0,0) xs

step (s, ln) a = (s + a, ln + 1)

strict_mean :: [Double] -> Double

strict_mean xs = s / fromIntegral ln

where (s, ln) = foldl' step (0,0) xs

step (!s, !ln) a = (s + a, ln + 1)

main :: IO ()

main = do

-- generate random test data

seed <- newIOGenM (mkStdGen 1729)

test_values <- replicateM 500000 $ uniformRM (0,500000) seed

-- sleep for a second

let wait = threadDelay 1000000

-- now run

print $! lazy_mean test_values

wait

print $! stricter_mean test_values

wait

print $! strict_mean test_values

We define three functions, each of which calculate a geometric mean from a list

of Doubles. lazy_mean uses a lazy left fold, stricter_mean uses a strict

left fold but will still leak memory because foldl' evaluates the result of

step to WHNF. step returns a tuple whose WHNF is a tuple

constructor. Thus, stricter_mean will leak memory because the elements of

the tuple are still lazy. strict_mean fixes this by adding bang patterns

inside the tuple, thereby forcing the elements to evaluate to WHNF; which is

just a value for Double.

GHC is good at spotting such code patterns so we’ve turned off optimizations

with the OPTIONS_GHC -O0 pragma.

2.6.3.6. The Setup¶

Using Eventlog requires three pieces of setup. First, you must build your

programs with the -eventlog -rtsopts -prof GHC flags (or alternatively set

profiling: True in cabal.project or enable library-profiling and

executable-profiling in stack.yaml.). For example:

benchmark pointerChasing

type : exitcode-stdio-1.0

default-language: Haskell2010

ghc-options : -fforce-recomp -threaded -rtsopts -prof -eventlog

build-depends: base >= 4.15

, containers

, deepseq

, gauge

, random

hs-source-dirs: bench/PointerChasing

main-is: Main.hs

Second, you must pass the RTS flag -l to your program and additional RTS

flags that describe which events to track. Lastly, you must pass RTS flags to

describe the kind of heap information to collect. Here are some examples of RTS

flag combinations:

<program> +RTS -hy -l-agu -RTS: Do not track all possible events (-a), but track all garbage collector events (g), all user events (u), and produce a heap profile by type (-hy).<program> +RTS -hr -la -RTS: Trace all possible events (a) and produce a heap profile by retainer (-hr).<program> +RTS -hb -l-asu -RTS: Do not track all possible events (-a), but track all scheduler events (s), all user events (u), and produce a heap profile by biography (-hb).

2.6.3.7. Visualizing the Heap: Eventlog by Type¶

To view the heap profile we’ll use eventlog2html. To begin we’ll inspect the heap by type. Our initial goal is to determine if we have a memory leak and if so which type is leaking. Here is the cabal file entry and invocation:

Note

For subsequent runs, we will elide the complete output

$ cabal bench pointerChasing --benchmark-options='+RTS -hy -l-agu -RTS'

Build profile: -w ghc-9.2.4 -O1

In order, the following will be built (use -v for more details):

- lethargy-0.1.0.0 (bench:pointerChasing) (first run)

Preprocessing benchmark 'pointerChasing' for lethargy-0.1.0.0..

Building benchmark 'pointerChasing' for lethargy-0.1.0.0..

[1 of 1] Compiling Main ( bench/PointerChasing/Main.hs, /home/doyougnu/writing/iohk/hs-opt-handbook.github.io/code/lethargy/dist-newstyle/build/x86_64-linux/ghc-9.2.4/lethargy-0.1.0.0/b/pointerChasing/build/pointerChasing/pointerChasing-tmp/Main.o )

[1 of 1] Compiling Main ( bench/PointerChasing/Main.hs, /home/doyougnu/writing/iohk/hs-opt-handbook.github.io/code/lethargy/dist-newstyle/build/x86_64-linux/ghc-9.2.4/lethargy-0.1.0.0/b/pointerChasing/build/pointerChasing/pointerChasing-tmp/Main.o )

Linking /home/doyougnu/writing/iohk/hs-opt-handbook.github.io/code/lethargy/dist-newstyle/build/x86_64-linux/ghc-9.2.4/lethargy-0.1.0.0/b/pointerChasing/build/pointerChasing/pointerChasing ...

Running 1 benchmarks...

Benchmark pointerChasing: RUNNING...

250137.43193906464

250137.43193906464

250137.43193906464

Benchmark pointerChasing: FINISH

$ eventlog2html pointerChasing.eventlog

$ firefox pointerChasing.eventlog.html

We ask cabal to run the benchmark, and generate an eventlog of only (-a) user (u) and GC (g) events with a heap profile by type (-hy); which yields the following heap profile:

Note

The heap profile is not a static image! Try clicking through the interactive output from eventlog2html along with the text.

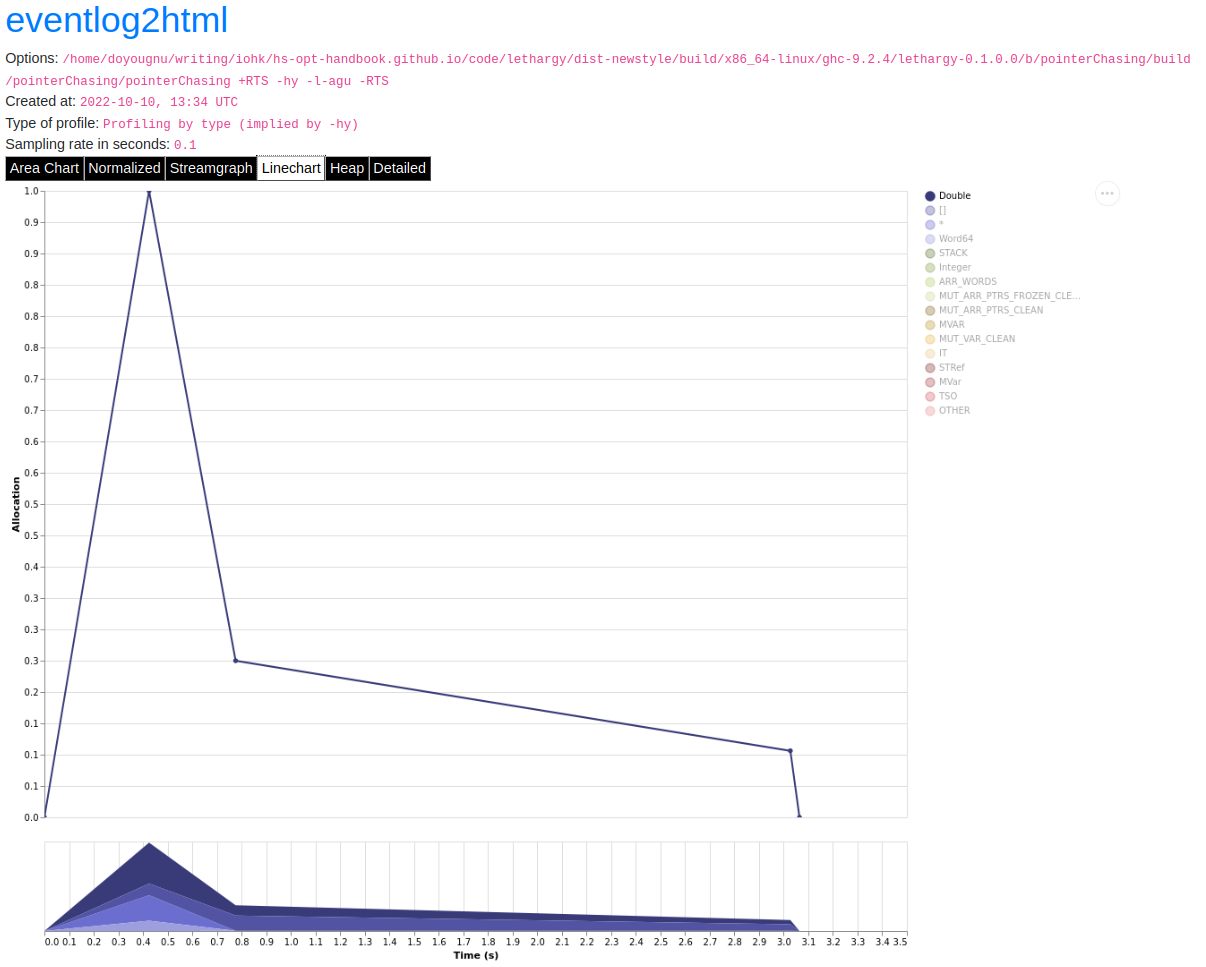

The heap profile is similar to profiles generated by traditional tools with some notable exceptions. First, this is a more interactive plot; for example, you can hover your mouse over a section of the profile and a popup will describe the corresponding description from the legend. You can also select an element on the legend to filter the plot to only that element. Second, eventlog2html produces more plots than just the area chart. It produces a normalized area chart, a streamgraph, a linechart, a heap breakdown by size of allocations (not count), and a detailed heap breakdown by every element in the legend.

Each chart serves different purposes and are useful; to show a particular chart, click its name in the black bar above the main plot area.

The normalized area chart shows the portion of allocations by type. This

makes it easy to see that after 0.8 seconds ~60% of allocations are of type

[]. Use the normalized area chart to view the composition of the heap at a

given time.

The streamgraph is similar to the normalized area chart, except that streamgraph’s show the evolution of allocations by a breakdown, such as type, by time.

From the streamgraph we can easily see that in the first 0.8 seconds our toy

program allocates a lot of Double, then after 0.8 seconds Double

decreases and most of the heap is []. You should use the streamgraph when

you want to view how a particular element in the heap changes over time.

The normalized linechart shows a breakdown of what is increasing over time.

The linecharts are noisy, fortunately we can filter to see exactly what type of

data on the heap is increasing over time. For example, here is a snapshot of the

streamgraph where I’ve filtered for Double:

Notice the triangular shape that smooths out. Here is the same plot only

filtered for []:

Notice the roughly triangular shape. Recall that these linecharts are

normalized so we are not getting a raw portion of allocations on the heap,

rather the chart displays what portion of the heap is composed of each type.

This makes it easy to see that we actually have two memory leaks: one for

Double and one for []. Both types show a triangular profile shape which

is a classic indication of a memory leak. It occurs because lazy_mean builds

up a lot of thunks; increasing allocations on the heap and producing the rising

edge, the program reaches a point where the thunks must be evaluated; producing

the top of the triangle, and then begins evaluating them thus decreasing the

allocations on the heap and yielding the descending edge. We could have observed

this pattern in the other plots, but the normalized linechart directly shows it.

Use the linechart when you want to view the composition of the heap by element

over time.

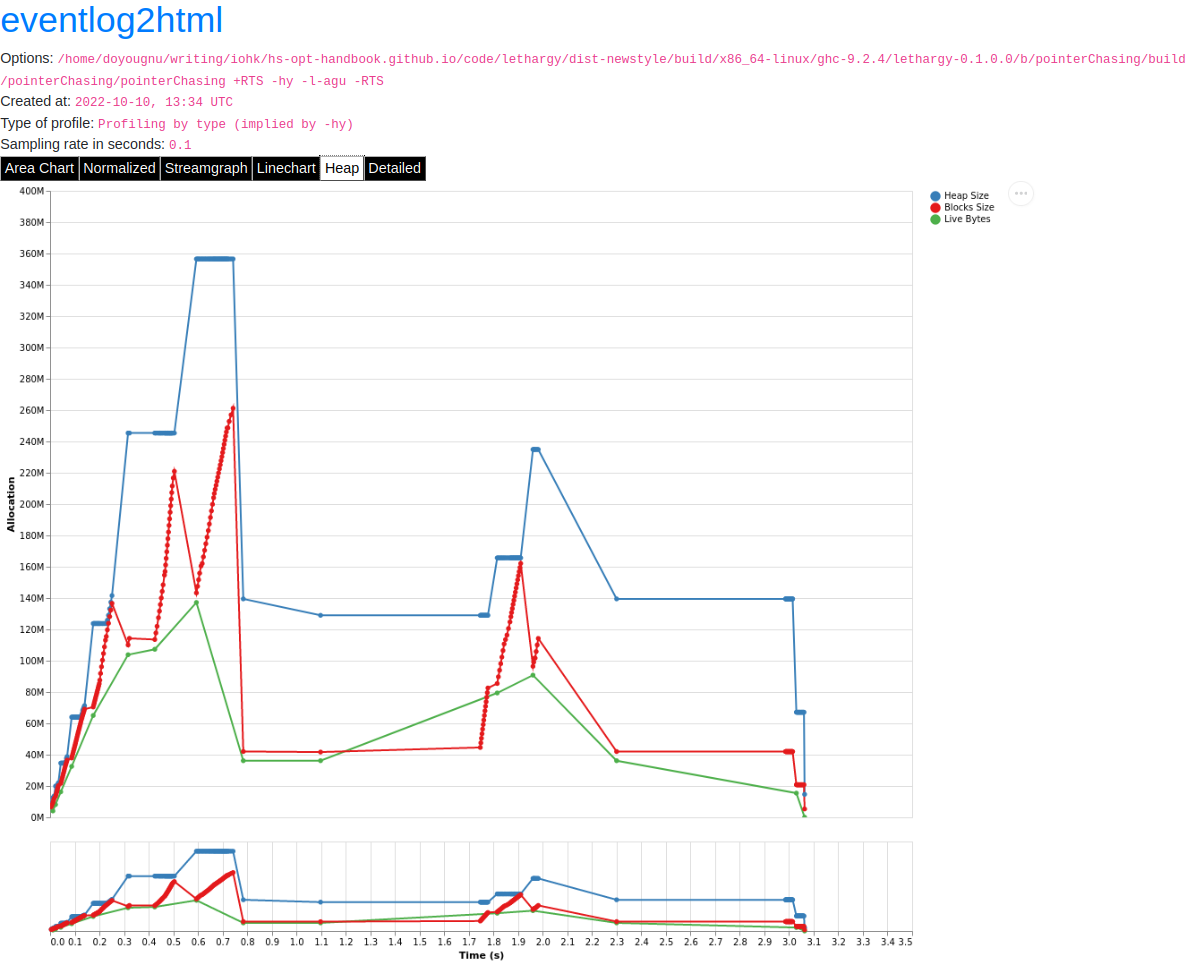

The heap plot shows the total heap size and the block and live bytes size over time. It is useful to see the total size of the heap at a particular time. We present it here for our toy program but don’t comment on it further:

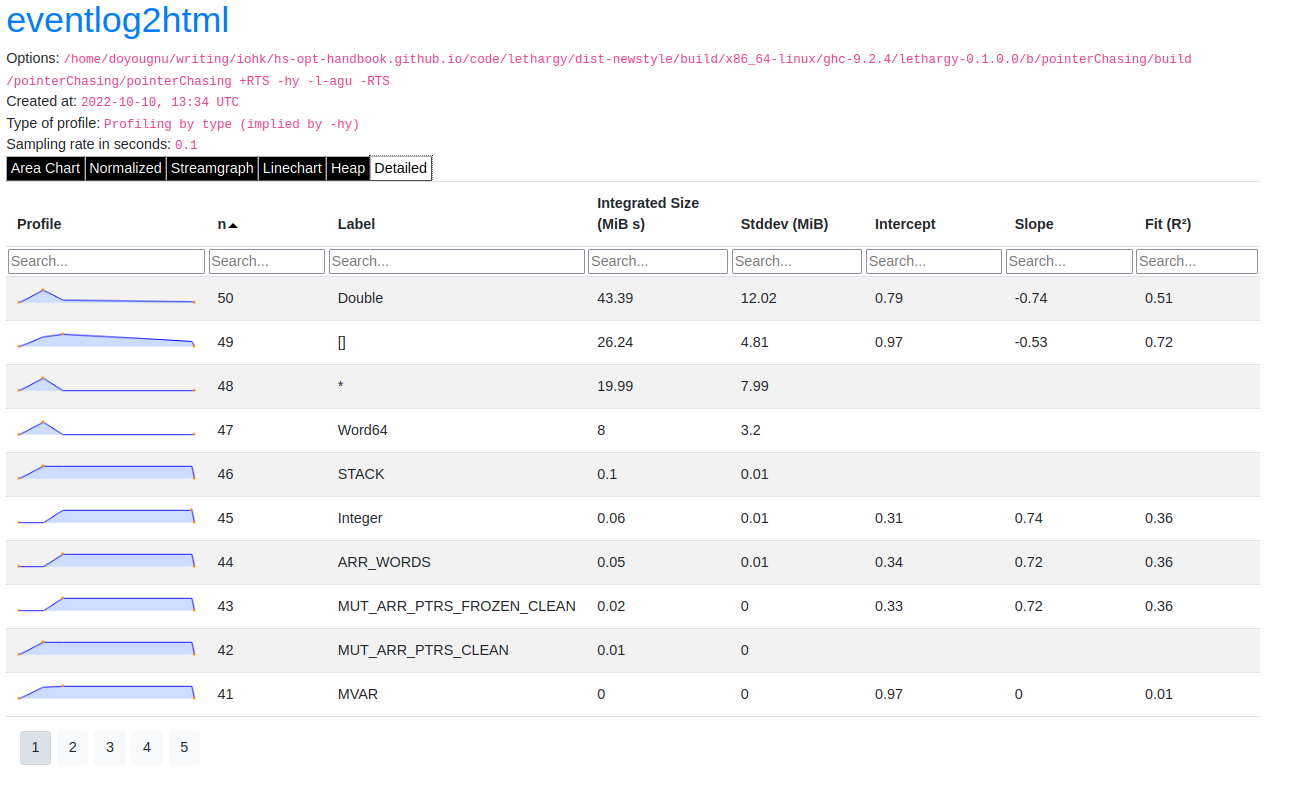

The last kind of information generated by eventlog2html, the detailed view, is one of the most useful visualizations. Here is the detailed view for the toy program:

The detailed view is a searchable table of the heap profile showing exactly the total allocations attributable to the element (in this case the type), and extra statistical information. You should use the detailed heap breakdown to inspect a particular element of the heap profile that you might already suspect and therefore can search. For our toy example, the detailed view is not that useful because we can clearly see the culprits from the other views. However for a complicated heap profile with numerous kinds of heap objects, the detailed view provides an easy way to search and inspect a particular heap object which may be buried in noise.

2.6.3.8. Adding Our Own Events¶

Thus far we have seen memory leaks coming from the types Double and [],

but we have not yet distinguished in the profile between lazy_mean,

stricter_mean, and strict_mean. Consider these functions as different

phases of the toy program; it would be useful to have an indicator in the heap

profile that delineates between such phases. For example, such a marker would

allow us to say “Ah! Phase foo does excessive allocation due to leaking

Double”. This is the purpose of traceMarker and traceMarkerIO in

Debug.Trace in the base library. Both functions allow us to emit a custom

marker to the eventlog which will then be rendered by eventlog2html. We’ll

demonstrate both traceMarker in our functions and traceMarkerIO in the

main function. Furthermore, we’ll add some more wait statements to avoid a

collisions between markers and the y-axis. Here is the marker version of the toy

program:

module Main where

import Data.List (foldl')

import System.Random (mkStdGen)

import System.Random.Stateful (newIOGenM, uniformRM)

import Control.Concurrent (threadDelay)

import Control.Monad (replicateM)

import Control.DeepSeq (force)

import Debug.Trace (traceMarker, traceMarkerIO)

lazy_mean :: [Double] -> Double

lazy_mean xs = traceMarker "Begin: lazy_mean" $ s / fromIntegral ln

where (s, ln) = foldl step (0,0) xs

step (s, ln) a = (s + a, ln + 1)

stricter_mean :: [Double] -> Double

stricter_mean xs = traceMarker "Begin: stricter_mean" $ s / fromIntegral ln

where (s, ln) = foldl' step (0,0) xs

step (s, ln) a = (s + a, ln + 1)

strict_mean :: [Double] -> Double

strict_mean xs = traceMarker "Begin: strict_mean" $ s / fromIntegral ln

where (s, ln) = foldl' step (0,0) xs

step (!s, !ln) a = (s + a, ln + 1)

main :: IO ()

main = do

let wait = threadDelay 100000

-- create a delay at the beginning of the program, if we don't do this then

-- our marker will be merged with the y-axis of the heap profile

wait

traceMarkerIO "Bench Initialization"

-- generate random test data

seed <- newIOGenM (mkStdGen 1729)

test_values <- replicateM 500000 $ uniformRM (0,500000) seed

traceMarkerIO "End Bench Initialization"

wait

-- now run

print $! lazy_mean test_values

traceMarkerIO "End lazy_mean"

wait

print $! stricter_mean test_values

traceMarkerIO "End stricter_mean"

wait

print $! strict_mean test_values

traceMarkerIO "End strict_mean"

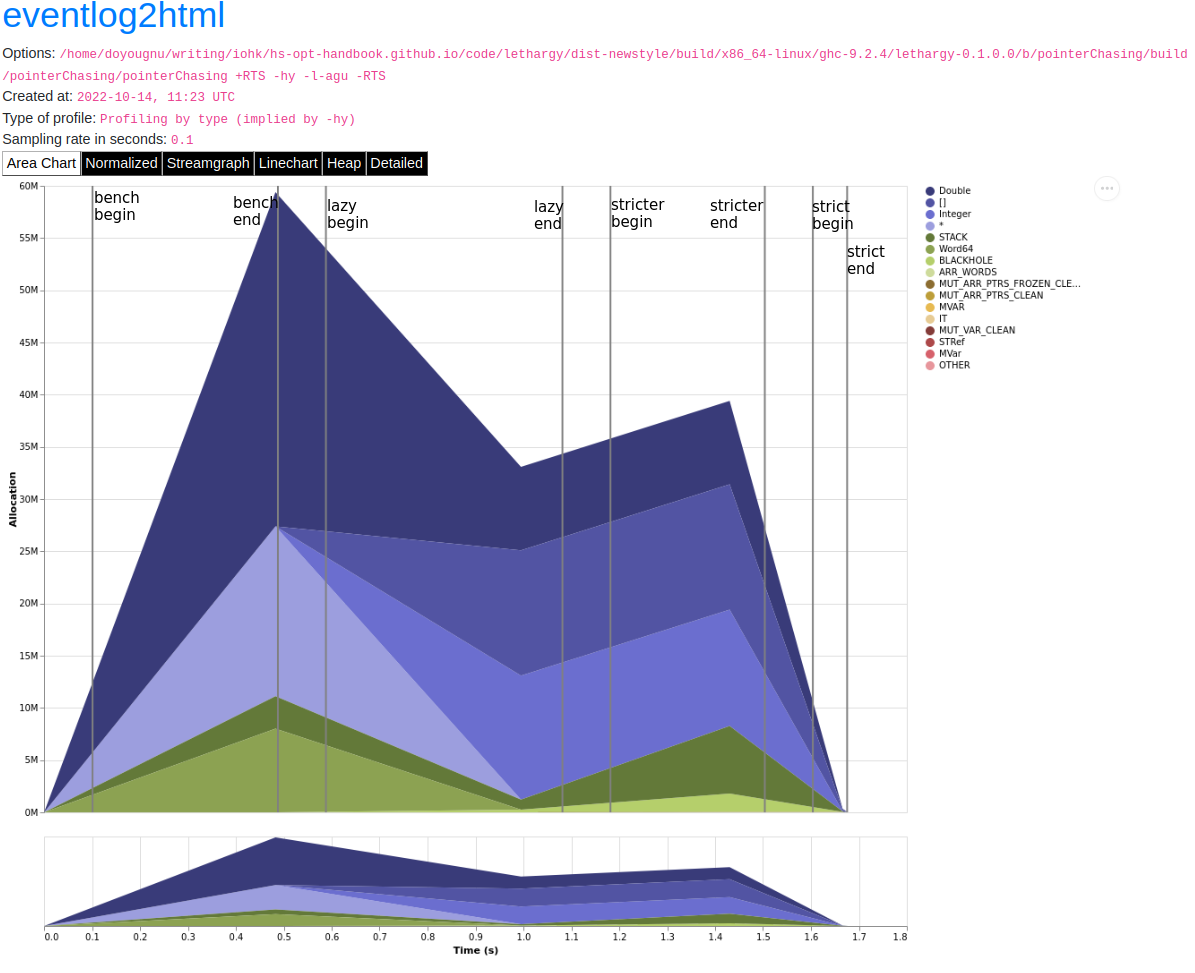

We add markers in two areas: in the beginning of each function and after each function call in main including the benchmark setup. Now let’s view the heap profile:

The gray lines that have been added to the profile are our markers. The

String input to traceMarker and traceMarkerIO is visible by hovering

the mouse over the marker. Here is a snapshot where I’ve manually added the

labels to how the popups statically:

We can make several important observations from this profile:

First, we can observe the difference in runtime between these functions by

comparing the horizontal space between the “Begin” and “End” markers. For

example, notice how close the begin and end markers are for strict_mean

compared to lazy_mean. From the x-axis we can see that strict_mean

finishes in about 0.1 seconds, while lazy_mean finishes in about 0.3

seconds.

Second, the ascending side of the first memory leak (the first triangle) comes

surprisingly from the benchmark setup, because the marker occurs before the peak

of the triangle. We should expect some allocation at the beginning of our

program (we need to have data to operate on after all!), but the heap should

flatten out (because the test data finishes allocation) until lazy_mean is

called.

Third, after the call to lazy_mean allocations decrease. This is further

evidence of a memory leak in the benchmark setup. If we had all values from

test_values fully evaluated and in memory when lazy_mean was first

called, then we would expect heap allocations to increase because we know that

lazy_mean is leaky. However, we observe the opposite; lazy_mean

reduces allocations until the heap levels out around 0.90 seconds and ~37M

allocations right before lazy_mean ends. The point at which the allocations

level out, is the point when lazy_mean finishes consuming thunks introduced

by the benchmark setup and finally performs the arithmetic computation. Thus, we

can conclude three things: First, a strict benchmark setup should allocate ~37M

on the heap, because this is the amount of allocations after lazy_mean has

consumed all the thunks; Second, the actual wall time for a strict lazy_mean

should be around 0.1 seconds because this is the duration of time between the

point at which lazy_mean has consumed all the thunks and when lazy_mean

ends. Third, notice that a known-leaky function did not appear to be leaky

because of another memory leak effectively hid it. This tells us that the memory

leak in lazy_mean is not comparable to the leak in the benchmark sweet. For

if it were comparable then we would have observed a rising edge after the

lazy_mean begin marker.

Let’s fix the benchmark setup memory leak by forcing strict IO with evaluate

and force from Control.Exception and Control.DeepSeq respectively. A

simple one line change in main:

module Main where

import Data.List (foldl')

import System.Random (mkStdGen)

import System.Random.Stateful (newIOGenM, uniformRM)

import Control.Concurrent (threadDelay)

import Control.Monad (replicateM)

import Control.Exception (evaluate) -- new

import Control.DeepSeq (force)

import Debug.Trace (traceMarker, traceMarkerIO)

-- ... --

main :: IO ()

main = do

let wait = threadDelay 100000

-- create a delay at the beginning of the program, if we don't do this then

-- our marker will be merged with the y-axis of the heap profile

wait

traceMarkerIO "Bench Initialization"

-- generate random test data

seed <- newIOGenM (mkStdGen 1729)

test_values <- fmap force (replicateM 500000 $ uniformRM (0,500000) seed) -- new

>>= evaluate

traceMarkerIO "End Bench Initialization"

wait

-- now run

print $! lazy_mean test_values

traceMarkerIO "End lazy_mean"

wait

print $! stricter_mean test_values

traceMarkerIO "End stricter_mean"

wait

print $! strict_mean test_values

traceMarkerIO "End strict_mean"

which produces:

No difference! The only remaining source of possible thunks in test_values

is uniformRM and the generation of seed. So we’ll remove any possible

lazy IO from that call:

main :: IO ()

main = do

let wait = threadDelay 100000

-- create a delay at the beginning of the program, if we don't do this then

-- our marker will be merged with the y-axis of the heap profile

wait

traceMarkerIO "Bench Initialization"

-- generate random test data

!seed <- newIOGenM (mkStdGen 1729) -- new

let genValue = fmap force uniformRM (0,500000) seed >>= evaluate -- new

test_values <- replicateM 50000 genValue >>= evaluate . force -- new

traceMarkerIO "End Bench Initialization"

wait

-- now run

print $! lazy_mean test_values

traceMarkerIO "End lazy_mean"

wait

print $! stricter_mean test_values

traceMarkerIO "End stricter_mean"

wait

print $! strict_mean test_values

traceMarkerIO "End strict_mean"

which produces an empty heap profile!:

The profile is empty because our sampling rate is too low now that we’ve removed

those thunks. Let’s sample 100x more frequently by setting the -i RTS flag.

The invocation now becomes:

$ cabal bench pointerChasing --benchmark-options='+RTS -hy -l-agu -i0.001

-RTS'; eventlog2html pointerChasing.eventlog && firefox pointerChasing.eventlog.html

and produces this heap profile:

Much better! There are several things to point out. The y-axis has reduced to

~7M maximum, and the x-axis has also reduced from 1.8 seconds to 0.9 seconds. We

can clearly see the memory leaks from lazy and stricter now. In fact,

lazy has a total of three memory leaks, and stricter has two. Because

our program is relatively simple, there are not many sites where these leaks

could originate. We’ll focus on stricter_mean and add markers to the source

of the remaining leaks. We’ll also remove lazy_mean but keep strict_mean

for comparison . Here is stricter_mean reproduced to refresh your memory:

stricter_mean :: [Double] -> Double

stricter_mean xs = traceMarker "Begin: stricter_mean" $ s / fromIntegral ln

where (s, ln) = foldl' step (0,0) xs

step (s, ln) a = (s + a, ln + 1)

We observed two leaks. We know that the fold should produce one leak because

foldl' evaluates the accumulator to weak head normal form, and the step

function does not evaluate the values inside its input (,), thus

accumulating thunks in the elements of the tuple. Let’s add markers to verify

this behavior:

stricter_mean :: [Double] -> Double

stricter_mean xs = (traceMarker "s" s) / fromIntegral (traceMarker "ln" ln)

where (s, ln) = foldl' step (0,0) xs

step (s, ln) a = (s + a, ln + 1)

which yields:

Now we can see that the call to ln reduces a lot of the heap. Let’s make

ln strict in step and observe the difference in the heap profile:

stricter_mean :: [Double] -> Double

stricter_mean xs = (traceMarker "s" s) / fromIntegral (traceMarker "ln" ln)

where (s, ln) = foldl' step (0,0) xs

step (s, !ln) a = (s + a, ln + 1)

and now we have:

Notice the y-axis has further reduced and that the marker for ln has

disappeared. The marker is still in the profile (you can check the eventlog

file), but because ln doesn’t force any thunks the marker is shadowed by the

end stricter_mean marker. We still have a leak after s, but this was

expected. Let’s make sure this is coming from s by making s strict:

stricter_mean :: [Double] -> Double

stricter_mean xs = (traceMarker "s" s) / fromIntegral (traceMarker "ln" ln)

where (s, ln) = foldl' step (0,0) xs

step (!s, !ln) a = (s + a, ln + 1)

which yields:

stricter_mean still doesn’t run in constant heap as the heap decreases

during and after calling it, but it is difficult to see exactly what is

decreasing. This situation is exactly why the detailed heap view is useful.

Checking the detailed view of the latest profile shows Double and [] to

be constant, but shows * decreasing. * is the symbol the heap profiler

emits for closures that have an unknown type. But the toy program is completely

monomorphic and has known types, so where do we have an unknown type? The only

code in the toy program that doesn’t have a precise type is in the benchmark

setup, and specifically this line:

...

seed <- newIOGenM (mkStdGen 1729)

...

where newIOGenM returns a polymorphic type that is implemented as an

IORef, that is, a value the profiler doesn’t have access to! Thus, forcing

this value should remove the memory leak. Our final main is:

main :: IO ()

main = do

let wait = threadDelay 100000

-- create a delay at the beginning of the program, if we don't do this then

-- our marker will be merged with the y-axis of the heap profile

wait

traceMarkerIO "Bench Initialization"

-- generate random test data

!seed <- newIOGenM (mkStdGen 1729) -- new

let genValue = fmap force uniformRM (0,500000) seed >>= evaluate

test_values <- replicateM 50000 genValue >>= evaluate . force

traceMarkerIO "End Bench Initialization"

wait

traceMarkerIO "Begin stricter_mean"

print $! stricter_mean test_values

traceMarkerIO "End stricter_mean"

wait

print $! strict_mean test_values

traceMarkerIO "End strict_mean"

which produces the final heap profile:

We could further investigate but our heap is now constant across

stricter_mean validating the lazy tuple hypothesis.

2.6.3.9. Summary¶

In sum, we’ve demonstrated heap profiling using GHC’s eventlog and

eventlog2html. Eventlog records event specific data produced by GHC as a

function of walltime. One can embed and emit custom events using the functions

traceEvent and traceEventIO, and add runtime markers to the eventlog

with traceMarker and traceMarkerIO in base. These functions and the

better visualizations of eventlog2html make eventlog a powerful tool when

investigating the runtime behavior of a program. In particular when finding,

fixing, and debugging memory leaks or when correlating heap information to a

particular function or phase of the program.

2.6.3.10. References and Further Reading¶

The eventlog section in the GHC User’s Guide.

The eventlog2html home page.